Government formation: Can a 7% annual reduction in emissions be achieved

Government formation talks are centred around an increase in climate ambition to a 7% reduction per year.

MaREI Research Fellow Paul Deane reflects on the proposal, gives numbers and suggests what is needed to have an increased chance of success.

Success in climate policy is measured in delivered reductions rather than rhetoric.

Ireland has scored high in the latter and the worst in Europe in the former

In 2008 Ireland committed to the most ambitious climate targets in Europe and by 2020 missed that target by the largest amount of any member state.

Ireland is again looking to an increased level of ambition for 2030 with government formation discussions centred around a 7% reduction in greenhouse gases per year to 2030.

The task is without parallel.

Ireland has only ever delivered significant emissions reduction during the recession or by closing an industrial plant.

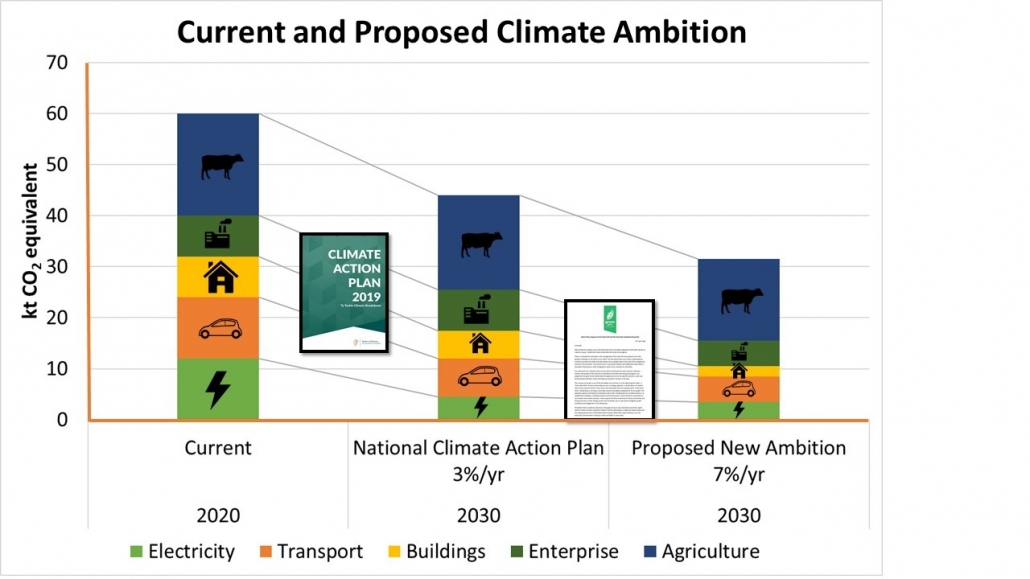

The current Government Climate Action Plan (CAP) aims to reduce all greenhouse gas emissions by 3% per year from 2020 delivering 90 million tonnes in cumulative emissions reduction to 2030 and moves Ireland’s annual greenhouse gas emissions from 61 million tonnes to 45 million tonnes for the year 2030

The proposed target of 7% will require a doubling of this ambition delivering in 5 years what the CAP said it would deliver in 10 years and requires an additional 100 million tonnes in cumulative emissions reduction.

The narratives on climate action are compelling; most people want action, however, the numbers are stark and convincing the public to act is something that must be achieved.

The proposed ambition of a 7% reduction per annum will require at least a doubling of the committed 30 billion euro investment in climate action in the period to 2030.

This is approximately an additional investment of 600€ per annum per Irish citizen

If the task is to be successful, political representatives must learn from the lessons of the past and plan for the future where difficult decisions and trade-offs must be made.

In the period to 2020, a lack of policy focus on transport, heat and agriculture which account for 80% of Ireland’s national emissions and 100% of our European emissions obligations was key to missing our targets

The leadership shown in the successful policy area of renewable electricity must now be replicated across all sectors and this will require a new approach with a particular focus on demand-side emissions.

Demand-side emissions reduction are more challenging and expensive than supply-side measures because the number of actors is greater, the emissions reductions are incremental and take longer to achieve.

Within Ireland’s ETS sector, 130 installations account for one-quarter of total emissions while the remaining 75% of emissions are produced by a heterogeneous mix, comprising of over 1 million households, thousands of small businesses and over 130,000 farms.

From a policy perspective, fragmented political support, piecemeal programmes and myopic policies must be avoided as they amplify uncertainty, increase costs and decrease the probability of success.

Research shows that a significant impact on achieving targets is the cost of finance rather than technologies choices. This must be reduced as much as possible.

Investment in emissions reduction, be they supply or demand side, are capital intensive with high upfront costs.

This requires long term policy support that must go well beyond the political cycle.

Within each individual sector, a number of options can be considered to deliver emissions reduction over and above what is already planned for in the CAP. [Emissions reductions are point estimates for one year]

Electricity:

Increasing renewable electricity ambition beyond the planned 70% for 2030 has open physical and logistical challenges however an estimate 1 million tonnes of projected emissions could be avoided if all Data Centres were mandated for 24*7 renewable energy supply rather than synthetic offsetting.

Beyond this, carbon capture and geological storage of emissions may be required for the power sectors and this should be investigated.

Transport:

Delivering extra emissions reduction over and above the CAP will require supply-side measures such as increasing the biofuel obligation (to E10 and B12) to be fast-tracked.

The introduction of “drop-in” biofuels such as hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) as done at scale in Sweden should be considered.

Blending one litre of HVO with every 9 litres of diesel could reduce emissions by 0.8 million tonnes

Encouraging remote working is important but impacts are often overstated; doubling the number of people working from home could deliver an additional 0.3 million tonnes of reduction.

Heating:

The CAP targets 500,000 homes to be retrofitted by 2030. This is approximately 200 home completions each day.

Increasing this to the suggested level of 350 per day would deliver an additional 0.2 million tonnes per year in reductions.

This will require an extensive skills and training program coupled with strict and frequent auditing for compliance of retrofitting standards and quality. It is also unclear how it will be financed.

Agriculture:

Giving rural families better options and a certain future is an important element to more financially and environmentally sustainable farming.

Forestry planting ambitions within the CAP will likely struggle as it underestimates the cultural attachment to land in Ireland

Bioenergy production of renewable gas could displace emissions in both industry, buildings, transport, manure management and chemical fertilizer use and deliver approximately 0.7 million tonnes of savings in 2030.

This will require strong, long term financial support as well as the swift introduction of strict compliance, certification and monitoring procedures to ensure sustainability.

Managing Expectation:

Ireland is unlikely to achieve a 7% reduction in annual emissions however success should be measured in cumulative emissions reduction from 2020 rather than annual intervals which are swayed by weather and interrupted by social events as we are seeing with the current crisis.

To increase chances of success strict monitoring of progress will be required. Increased ambition is not enough – actual emissions reductions are required.

This challenge is made difficult because national accounts on emissions take 2 years to produce.

Monthly or 6 month timelines and milestones for sectoral targets in terms of houses renovated, km of cycle lane built etc. should be used a proxy for emissions

Above all, expectations may have to be managed and plans may have to be flexible

The history of energy transitions often shows us that what was once thought impossible can be achieved, but it usually takes much longer than expected