The challenge of allocating Ireland’s carbon budget among sectors

Written by Professor Hannah Daly in MaREI@UCC

The Irish Government is currently deliberating on how to allocate nationally-adopted carbon budgets among sectors, a task which is understandably causing heated debates. The key debate is what carbon budget will be allocated to the agriculture sector, which is worth around 40% of overall greenhouse gas emissions (depending on how land use emission, “LULUCF”, is taken into account).

Ireland’s carbon budgets create a legally-binding ceiling on overall GHG emissions between 2021-25 and 2025-30, consistent with overall GHGs falling by 51% between 2018 and 2030. We are already around one-quarter way through the first carbon budget period and indications from the EPA are that emissions have not even started to fall, not to mind at the rapid pace required to get us below the carbon budget.

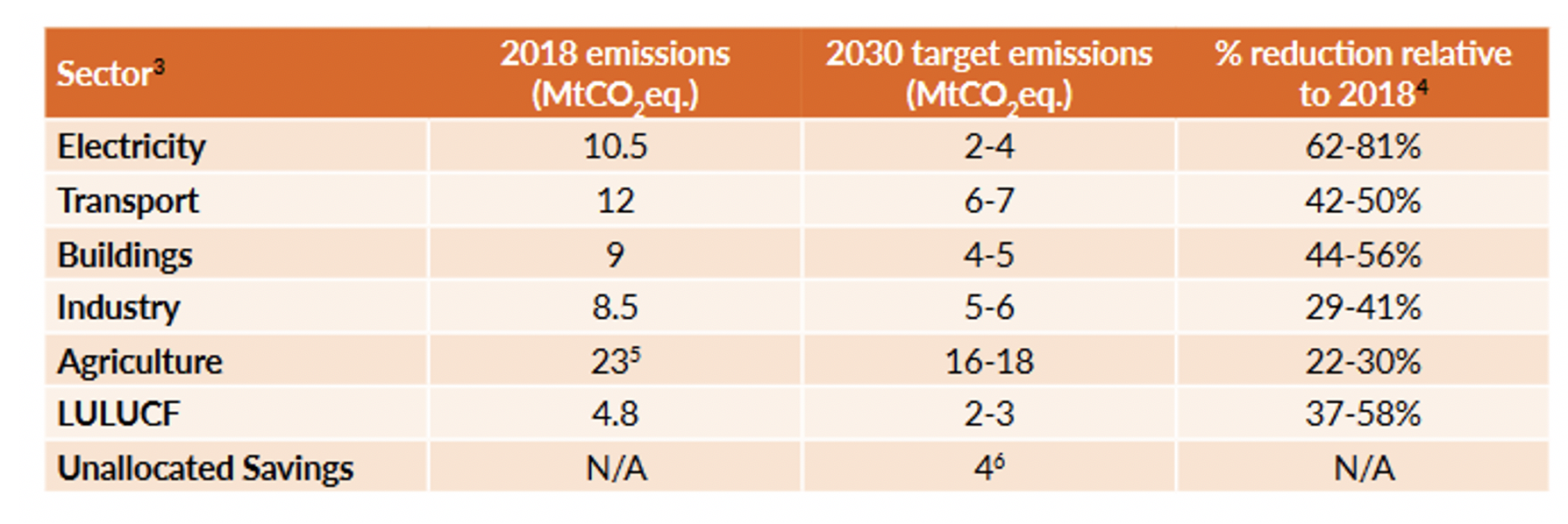

Table 1: Range of emission reduction targets proposed in Climate Action Plan 2021. Each sector needs to reach the lower target (highest reduction) in order to meet the carbon budgets.

Table 1: Range of emission reduction targets proposed in Climate Action Plan 2021. Each sector needs to reach the lower target (highest reduction) in order to meet the carbon budgets.

To prepare to meet the new challenging carbon budgets, the Climate Action Plan prepared by the Government in 2021 set out a range of actions and emissions savings in each sector (see the table to the left). It is clear from the mathematics that each sector needs to reach the lower of the proposed target ranges (in other words, meet the highest percentage reduction relative to 2018) for the overall target of reducing GHGs by 51% by 2030.

Energy systems modelling we have undertaken in UCC confirms that meeting the upper range of energy-related emissions reductions (that is, in electricity, transport, buildings and industry), collectively reducing greenhouse gas emissions by around 60%, will be enormously challenging and will probably require the fastest planned energy transition in history. I gave a talk to Engineers Ireland about our modelling the challenge of meeting the overall carbon budget target last year.

However, figures in the agriculture sector are negotiating that the carbon budget for their sector reflect the lower range of effort, or in other words, that the agriculture sector be allocated a larger share of the national carbon budget.

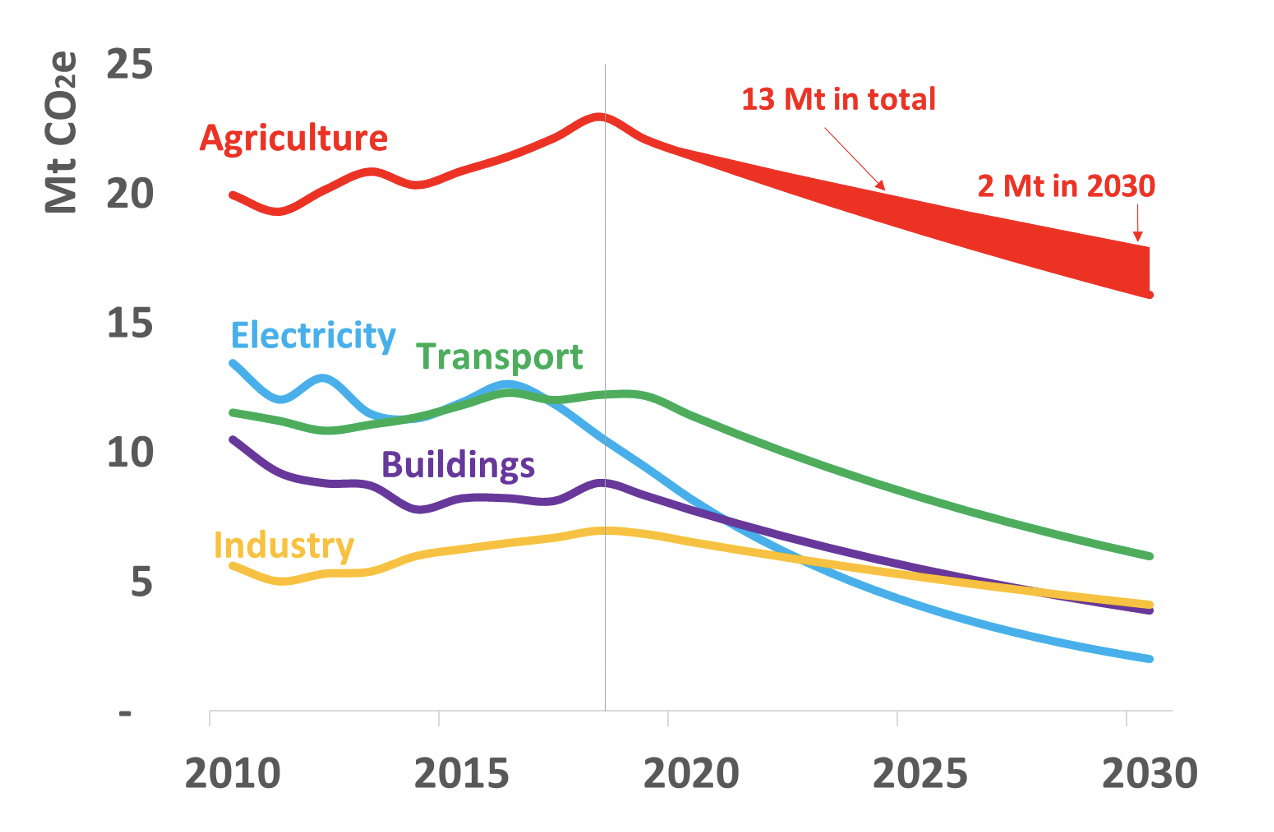

If the agriculture sector was allocated a target of reducing emissions by 22% rather than the maximum of the range, 30%, then additional savings will need to be found in other sectors, beyond the maximum of the ranges proposed in the Climate Action Plan, and instead of the energy system being required to reduce emissions by 68%, rather than 60%. It would require one or several sectors to have their overall carbon budgets reduced by about 13 Mt, and to reduce emissions in 2030 by a further 2 Mt.

An additional 2 Mt in 2030 may not seem large, but the energy system will already have to reduce GHGs to around 16 Mt – the additional 2 Mt represents a further 12% reduction beyond this extremely challenging target.

We have undertaken a new study to examine what would be required for the energy system to have a reduced carbon budget of 13 Mt (consistent with reducing overall emissions by 68% rather than 60%, to reflect the agriculture sector being allocated a 22% emissions reduction target rather than 30%.

The results show the very substantial increase in upfront costs and effort this would bring.

This chart illustrates the additional cost this decade – an additional €10 billion in upfront investment required by 2030, on top of €45 billion in energy system investment required just to meet the maximum target for the energy system.

This amounts to around €5000 in investment per household this decade, on top of already very substantial effort required.

The modelling work for this study also shows how having a lower carbon budget would increase the marginal abatement cost (which is a measure of the cost of the most expensive tonne of CO2 removed from the energy system) from about €450 per tonne to around €900 per tonne.

This analysis is underpinned by the TIMES-Ireland Model developed by the Energy Policy and Modelling Group at the Environmental Research Institute in UCC. This model has been peer-reviewed and published open-source, and was used to help inform the Climate Change Advisory Council’s deliberations on carbon budgets in 2021.

The figure to the right shows the proposed target in each sector (not including LULUCF and waste). The shaded red area represents the difference between the agricultural sector being allocated a 22% or 30% reduction target for 2030, which would need to be reduced in one of the other sectors (13 Mt cumulatively over the decade and 2 Mt in 2030).

The electricity sector is already required to reduce emissions by 80%, to 2 Mt, a figure which the industry claims is at the boundary of credibility. Claiming the 13 Mt deficit from this sector would require a zero-carbon power system in eight years, which is not credible.

If the gap was to be met by the transport sector, emissions from cars, trucks and vans would need to fall by two-thirds rather than halve. Already, to halve transport emissions requires nearly one million electric vehicles on the road, a doubling of biodiesel and a large reduction in passenger transport trips. Reducing transport emissions by a further 2 Mt in 2030 would be equivalent to taking all fossil-fuelled vans off the road, or a further 500 thousand private cars.

If the gap was met by buildings, emissions in the sector would fall by nearly 80% rather than the planned 56%. On top of the huge retrofit and electrification actions planned, another quarter of the housing stock would need to be zero-carbon. 2 Mt is equivalent to all emissions from heating public and private services in 2018.

Could the gap be met by industry? 2 Mt is about the same as the cement industry process emissions, or around 40% of emissions from all manufacturing. The sector already targets reducing CO2 by 40%; anything more would have huge ramifications for those industries.

While the agriculture sector is clear about the challenges it faces from achieving ambitious decarbonisation targets, it’s crystal clear that this challenge is not unique – every part of society will need to pull its weight, and both our energy, food and land systems will need to transform. Given the urgency of preventing climate breakdown that every sector will need to make very big changes, and agriculture is no exception.